By Satyaraja Dasa

The kindness of strangers played a pivotal role in ISKCON’s pre-history.

Last year I had the good fortune to meet Gopal and Sally Agarwal, an elderly couple who played a significant role in ISKCON’s origins. They are forever etched in the devotees’ collective memory as two of the Western world’s earliest recipients of Srila Prabhupada’s mercy. It was the Agarwals who hosted him in the fall of 1965, before ISKCON was even nominally born, giving him shelter, hospitality, friendship, and love. Indeed, for one month their home served as Prabhupada’s earliest refuge outside India.

As Prabhupada acquainted himself with the Agarwal home in Butler, in western Pennsylvania, he saw a typically quiet American town nestled in the hills, a town that has changed little since his brief visit those many years ago.

Last year, Nitai Dasa, a grand-disciple of Srila Prabhupada’s, organized a celebration in Butler to commemorate Prabhupada’s time there. Appropriately, the event was convened at the Butler Cubs Club, at 113 South McKean Street, the YMCA that served as Prabhupada’s sleeping quarters during his days with the Agarwals. In fact, the Agarwals were the guests of honor at the event. Sally addressed the audience of largely ISKCON devotees, including Radhanatha Swami, Varshana Swami, and Candrashekhara Swami. Dr. Allen Larson gave the keynote speech. Now a retired professor of philosophy at Slippery Rock College, in Butler, in 1965 he invited Prabhupada for his first college lecture in the West.

One of the lasting fruits of the Butler event, at least for me, was making contact with Sally and Gopal, charming and good-hearted people with unique and profound memories of Srila Prabhupada. For several months afterward, we kept in touch by phone and email, and they shared many wonderful stories about their time with my spiritual master. Although they never became devotees in the usual sense of the word, Prabhupada engulfed their consciousness, changing their lives and perceptions in innumerable ways. A detailed account of their interaction with Krishna’s pure devotee appears in Satsvarupa Dasa Goswami’s Srila Prabhupada-lilamrita, and this short article might serve as an addendum to that story.

The Mission Begins

A small occurrence can lead to a monumental event. A dry seed in hand may look insignificant, but inside is a plant-to-be. So it was when a businessman from Agra—Mathura Prasad Agarwal—offered a venerable and exceptional monk, whom the world would eventually know as His Divine Grace A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada, sponsorship in the Western world. As Srila Prabhupada undoubtedly told Mathura Prasad at the time, he had been instructed by his spiritual master to spread the timeless message of Krishna consciousness—the science of God realization—worldwide. The pious businessman could thus surmise that helping this particular sadhu would mean assisting him on his journey to the West; it would be the only assistance Prabhupada would need or want from him. Prabhupada would soon travel abroad and change religious history by founding the Hare Krishna movement.

ISKCON members know the story well: After an arduous journey by ship, landing first in Boston harbor and then in New York, Prabhupada emerged in the Western world, bringing centuries of tradition and the precious gem of Vedic knowledge for all who would have it. He was required by law to meet and stay with his sponsors, Mathura Prasad’s son Gopal and daughter-in-law Sally. The Agarwals held the legal documents enabling Prabhupada to enter America. They offered him their home in Butler, Pennsylvania, as his first foreign sanctuary.

It was 1965, and the couple was in their mid-30s, married only six years earlier. Sally, a Caucasian Methodist born in Pittsburgh, was just getting to know her husband’s Indian culture. She was excited that a real-life swami would be staying in their home.

As Sally tells it, the Agarwals received Prabhupada’s initial letter in early September, and he included a picture so that they might recognize him when he arrived.

“Using this picture,” relates Sally, “my husband met him in Pittsburgh, since he was coming in on the Greyhound bus from New York City. Gopal had worked it out with Traveler’s Aid to get him to Pennsylvania. So we met him. It was about midnight when they reached Bulter, and, poor fellow, he was tired from his constant journeying, and the only place we could set up for him was our couch.”

There wasn’t much of an alternative. The Agarwal residence, a small townhouse apartment, consisted of few rooms, with two upstairs bedrooms occupied by the two children, Kamla Kumari (their three-year-old daughter) and Brij Kumar (their newborn son). After Prabhupada left, the couple had two more children, Indu and Maya, born in 1969 and in 1971, respectively.

Since the Agarwal apartment had so little space—and because they didn’t want Prabhupada confined to their couch, night after night—they decided it would be better if he stayed at the YMCA, spending morning, noon, and evening with them until he was ready to call it a day. This was the Butler Cubs Club on South McKean Street, just a few blocks from the Agarwal home.

In a recent conversation with Sally, she told me about those first few weeks with Prabhupada:

He was so gentle, accommodating, and kind. I felt like he was Gopal’s father—a grandfather around the house, if you know what I mean. He played with Kamla and Brij. He just loved children, even when Brij teethed on his sandals! He just laughed and had a good sense of humor about everything. Sometimes he would tell us of his mission, but he always respected my Methodist background, never trying to convert me or to push his beliefs on us. He wasn’t talking about starting a movement or anything like that. But he was serious about distributing his books. He had brought them from India, and he saw his life’s mission as bringing this profound knowledge to the West, to reveal what he knew in the English language. We came to love his sincerity, his knowledge, and his warmth. I cried when he had to leave Butler.

Sally loves to mention, too, that her baby daughter may have been the first in the West to detect Prabhupada’s holiness: “Once, my three-year-old, Kamla, seeing Swamiji in the robes of a holy man, called him ‘Swami Jesus.’ He merely smiled and said, ‘And a child shall lead them.’”

A Swami in Butler

Soon after Prabhupada arrived, Sally hurried off to all the local newspapers, and shortly thereafter a feature article appeared in the Butler Eagle: “In fluent English, Devotee of Hindu Cult Explains Commission to Visit the West.” A photographer had come to the Agarwals’ apartment and had taken a picture of Srila Prabhupada standing in the living room, holding an open volume of Srimad-Bhagavatam. The caption read, “Ambassador of Bhakti-yoga.”

The article began:

A slight brown man in faded orange drapes and wearing white bathing shoes stepped out of a compact car yesterday and into the Butler YMCA to attend a meeting. He is A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swamiji, a messenger from India to the peoples of the West.

The article quoted Prabhupada as follows:

“My mission is to revive a people’s God consciousness,” says the Swamiji. “God is the Father of all living beings, in thousands of different forms,” he explains. “Human life is a stage of perfection in evolution; if we miss the message, back we go through the process again. …” If Americans would give more attention to their spiritual life, they would be much happier, he says.

At Prabhupada’s request, Gopal held a kind of open house in his apartment every night from six to nine. The family would invite friends and neighbors to hear “the Swami” talk about exotic India, and about Vedic philosophy and mysticism. The Agarwals knew many intellectuals, and people came from neighboring towns just to hear him speak.

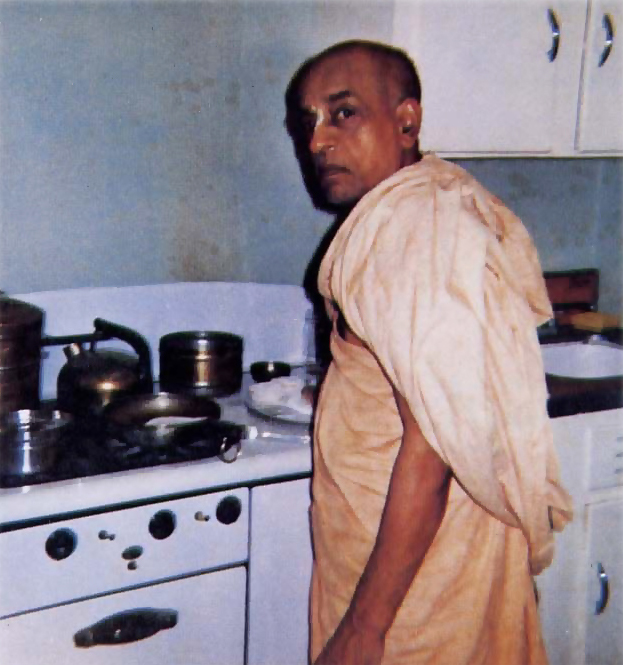

Lecturing to large groups was clearly among his many talents. But this was only his formal persona. The Agarwals saw another side, too, one that was quaint and friendly, down-home and endearing. For example, Gopal tells the story of how Prabhupada would cook lunch for them daily, demonstrating how to prepare meals in authentic Vaishnava style.

He had the curiosity and wonder of a child, too, says Sally: “He was fascinated by laundry machines, by washers and dryers, and the frozen vegetables in the freezer. Apparently, these were not common things in India, and he talked about them for hours and hours. He always talked about modern developments and how they could be used in God’s service.”

At times, Prabhupada’s presence in the Agarwal home led to minor challenges. Sally tells the story of when he washed his clothes in their upstairs bathroom:

“Oh man! I didn’t know it at the time, but he washed his two simple cloths every night. You see, he only owned two monk garments at the time, and every day he’d wash them. He would be busy in the bathroom sink upstairs, drenching the bathroom floor for the longest time—slop, slop, slop. Gopal had to go up there one day and explain to him that you can’t do that in America, you have to be careful with water. In India the floors are cement, mud, or clay, and so it doesn’t matter if you slop it up. But in our country, when the bathroom is on the second floor, it definitely matters! And then he spread his outfit, his two pieces of cloth, on the grass just outside our apartment complex, which was quite a sight in our local neighborhood.”

Still, Sally and Gopal deeply appreciated his presence in their home, and, increasingly, so did many others in the Butler community.

Sally reminisces in the Lilamrita about her own pleasant interactions with him:

He was the easiest guest I have had in my life, because when I couldn’t spend time with him he chanted, and I knew he was perfectly happy. When I couldn’t talk to him, he chanted. He was so easy, though, because I knew he was never bored. I never felt any pressure or tension about having him. He was so easy that when I had to take care of the children he would just chant. It was so great. When I had to do things, he would just be happy chanting. He was a very good guest. When the people would come, they were always smoking cigarettes, but he would say, “Pay no attention. Think nothing of it.” That’s what he said. “Think nothing of it.” Because he knew we were different. I didn’t smoke in front of him. I knew I wasn’t supposed to smoke in front of Gopal’s father, so I sort of considered him the same. He didn’t make any problems for anybody.

The First Preaching in the West

Prabhupada spoke to various groups in the Butler community, including the Lions Club, where he received a formal document proclaiming “Be it known that A. C. Bhaktivedanta Swami was a guest at the Lions Club of Butler, Pa., and as an expression of appreciation for services rendered, the Club tenders this acknowledgment.”

He also gave a talk at the YMCA and at St. Fidelis Seminary College in nearby Herman.

Professor Allen Larsen, then chairman of the philosophy department at Slippery Rock State College, also invited Prabhupada to lecture. A hundred students from three of his classes came to hear. Prabhupada appeared before them with his distinct otherworldly glow and full sannyasi garb—an uncommon sight in the West, and even more uncommon in Butler. He sat down and chanted the Hare Krishna maha-mantra. Then he stood and spoke—a formal but basic lecture on Krishna consciousness—and answered questions from the audience.

Professor Larsen remembers that the program lasted about an hour and forty-five minutes. At the celebration in Butler last year, he recalled:

When I first met him, he told me he had come to the U.S.A. to translate the Vedic scriptures, and as far as I knew that was his only aim of being here. We had tried to talk on the campus. It was a nice day, and he drew up his legs under him and sat in what you call a lotus position. He remarked that trees should be nut and fruit trees. They weren’t—they were just flowering trees, just for show, and I certainly agreed with that.

During our lapses in conversation he would use his prayer beads and recite a Krishna prayer which was hardly audible to me. Although I’ve forgotten many of the details of his talk, it was clear to me that he was a holy man. This just radiated out of his being. It was primarily his composure, his peacefulness, that led me to that conclusion. I had no idea that this quiet man would become a leader of a significant religious movement here and abroad. After all these years, that impression of a holy man has stayed with me.

The lectures in Pennsylvania were a testing ground, Prabhupada’s first indications of how his message would be received in America. The reception was promising. Sally and her husband encouraged him to repeat this formula elsewhere, and Professor Larsen expressed deep satisfaction with having hosted a genuine Indian sadhu.

The Movement Expands

After a month, Prabhupada left Sally and Gopal’s little hamlet, and the seeds of his mission had been sown. While there, he gained experience with American audiences. He saw that people were interested in his books and message, and also that he could endear himself to foreign people. Sally, especially, “came to love the Swami,” as she puts it.

In New York he struggled for almost six months, subjected to a bitterly cold New York winter, the theft of his simple belongings, and the abuse of a drug-crazed roommate. Yet his determination to bring about a spiritual revolution would soon bear fruit.

All the while he kept in touch with Sally and Gopal by letter. Especially Sally, since she was the more gregarious of the two, always ready to engage in conversation and personal exchange. Prabhupada’s correspondence with Sally is a matter of public record, and it is heartening to see his concern for her in those letters.

In May of 1966, Srila Prabhupada, with the help of just two followers, rented a storefront in New York’s Lower East Side, previously a novelty shop with the name “Matchless Gifts.” Early visitors to Srila Prabhupada’s new center were struck by the prophetic name. In July of 1966, he incorporated his institution, ISKCON.

Prabhupada always kept in touch with Sally. In fact, Sally notes that the “celebrity” of being one of Prabhupada’s first contacts in the West is downright fun.

“Our time with Swami broadened my mind a lot,” she says, “because I’m open to that kind of thing. I mean, it’s been a lot of fun. Maya, my daughter, was in the Dallas airport a couple of years ago when she was approached by a Hare Krishna selling the books, asking for a donation. And of course she said that she was Sally Agarwal’s daughter—you could imagine that devotee’s response. There was another occasion: One day Maya and I were in Madrid and there was a Hare Krishna group chanting right near us. But this time, we didn’t tell them who we were—we didn’t want all the commotion. But it’s been fun; it’s been a lot of fun.”

As influential advertising mogul Bruce Barton famously said, “Sometimes when I consider what tremendous consequences come from little things, I am tempted to think that there are no little things.” Mathura Prasad’s pious gesture to Krishna’s most important representative, and the kindness that both Gopal and Sally subsequently showed him in Butler, are certainly not “little things.” Indeed, the consequences of these gracious acts proved to be monumental.

Audio file of Sally Agarwal giving her memories of Srila Prabhupada’s first steps on American soil.Listen, Download

Gopal and Sally discuss Srila Prabhupada’s fascination with frozen foods and other sweet memories.Listen, Download

Comments